The Platform Workers Act: hard-won representation for gig workers poses opportunities and threats for the riders’ movement

Independent food delivery rider groups and collective action played a pivotal role in shaping the Act that was passed in September 2024, but the Act could restrict further organising efforts.

By Suraendher Kumarr

The Platform Workers Act was passed on 10th September 2024. It will see more than 70,000 platform workers, such as delivery workers, private-hire drivers and taxi drivers, grouped under a new category of workers that is distinct from employees and freelancers. The Act comprises 3 measures that will affect platform workers:

Give workers the option to contribute to their CPF. And as a result, also require platform operators to contribute to their CPF.

Provide workers with the right to claim financial compensation for injury at work.

Allow platform workers to form a Platform Worker Association (something like a union) to engage in collective bargaining with the platform operators.

In my conversations with food delivery riders, I get the sense that the Act is a step in the right direction. However, some serious concerns remain.

Key issues food delivery riders face

There are about 16,000 food delivery riders in Singapore. Like other platform workers, they have existed in a grey space. Platform operators call them “partners”, claiming to treat them as contractors and not workers. But is this the reality? Normally, contractors have the freedom to choose the jobs they wish to take. For example, they are free to reject jobs that they determine do not pay them enough. Contractors are normally able to negotiate the price the client is willing to pay them. Unlike workers in the traditional sense, contractors have the flexibility to decide when they work. “Be your own boss”, they say.

However, the reality for food delivery riders is far from this. In his speech at this year’s Labour Day Rally, 41 year old food delivery rider Andy Sng shared, “before the pandemic, we had some form of control. You could say we were our own boss. But after the circuit breaker, when restrictions are lifted, we are no longer our own boss.”

With the exception of Deliveroo, all platform operators punish riders if they reject orders assigned to them. Their AR/CR (acceptance rate/cancellation rate) rating declines and this means the algorithm assigns them fewer or lower fare orders. As Andy says, “If you decline too many orders, they (Foodpanda) will put you offline…and at times, even ban you.”

According to many riders, fares have declined significantly. Riders therefore feel the need to complete more trips (work longer hours) in order to earn a decent living. It is not uncommon to hear of riders working 6 or 7 days a week for 10 hours or more each day.

Not all riders get insured by the platform operator in the event of a work injury or illness. Insurance is tier-based - in other words, it depends on how many trips you have completed. Insurance is therefore not a right, but something you have to earn. Andy also articulated this in his speech: “When you sign the terms and conditions, you’re signing your life away. If you get into an accident, you’re on your own. If you are sick or there’s any issues at home, there is no annual leave, no MC.”

Food delivery riders, then, have the worst of both worlds - contractor and worker. They are treated like workers in that they are subject to the fares the platform operators dictate, and like contractors, they are left without any of the protections that workers are entitled to under the Employment Act.

Is the new Platform Workers Act good for workers?

Including platform workers under the Work Injury Compensation Act is long overdue. With this in place now, under the Platform Workers Act, insurance will no longer be a privilege based on performance, but a right.

The CPF policy in the Act is a significant improvement from what was initially proposed by the government in March 2022. In March, Senior Minister of State for Manpower Koh Poh Koon announced that the government was considering making CPF contributions mandatory for all delivery riders, which led to many riders voicing concerns that this would eat into their already depressed wages. The relaxed policy we see in the Platform Workers Act - where it is optional for those aged 30 and above - is therefore much better.

However, without any legislation to first protect riders’ fares, it is likely that platforms will further reduce fares to make up for lost revenue from providing riders with CPF. Several riders I spoke to have said that like workers in some other sectors who are protected under the Progressive Wage Model, riders should have a similar framework as well, which protects their fares. Workers Make Possible, SG Riders, NGOs like AWARE, and several Members of Parliament have all publicly supported the principle of a minimum fare. Many approaches to do this have been suggested. For example, Workers Make Possible, SG Riders and PSP MP Leong Mun Wai support the notion of a Minimum Fare Guarantee - a wage floor that platforms must abide by. AWARE and WP MP Louis Chua raised the idea of pegging the fare to the local qualifying salary.

In a bid to offset increased CPF contributions for low-income riders, the government announced that it will provide monthly cash assistance from 2025 to 2028. In 2025, when the Act comes into force, The Ministry of Manpower (MOM) will offset 100% of the workers’ share of CPF contributions for workers earning up to $3,000 per month. The cash support will decrease by 25% each year until 2028. Platform workers will have to make their own CPF contributions by 2029.

While this seems generous, the cash assistance provided by the government for low-income food delivery riders to transition to contributing to CPF is short-sighted. It provides a short-term cushion for the food delivery riders, only for them to face the full force of the CPF deductions from take-home pay after the expiry of the financial assistance. Unless a minimum fare guarantee or wage floor of some sort is negotiated by then, riders may face a very serious challenge coping with the rising cost of living with lower take-home earnings. The government’s approach with riders mirrors its approach to raising the GST. The government introduces a policy that burdens the people, and then introduces another temporary policy to alleviate the immediate burden it has imposed. Rather than GST or CPF cash vouchers that offset the pain of these increased costs or decreased wages, workers need structural change. In the case of the platform workers, the most important structural reform is a minimum fare guarantee.

It was encouraging to see two MPs raise the need for a solution on platform workers’ wages. PSP MP Leong Mun Wai raised the idea of a minimum fare guarantee. In response, Senior Minister of State for Manpower Koh Poh Koon said that this is for Platform Worker Associations (PWA) to bargain for once they are legally registered. The Platform Workers’ Bill outlines what such a body would look like. PWAs are to be authorised by the Ministry of Manpower, and do not need the mandate of the workers they are trying to represent. PWAs simply need a committee of seven people, of whom not everyone needs to be a platform worker. On one hand, some representation is better than no representation at all. At the very least, the framework of a PWA empowers such organisations to bargain for collective agreements with the platforms.

However, there are at least three problems with this framework for representation. Firstly, how can a PWA claim to represent riders with just seven members, when not even all seven need to be platform workers? It is ironic that a PWA needs to earn the mandate of MOM, but not of platforms workers, to be registered. Last year, the government said it accepts the recommendation for a process for PWAs to obtain workers’ mandate to represent platform workers. This would be through a secret ballot that requires a 20% quorum of eligible platform workers. However, this was not incorporated into the Platform Workers Act.

Secondly, with MOM having the power to authorise a group to become a PWA, is there room for a conflict of interest to arise? The PAP forms the government, and many PAP politicians are also members of NTUC. The three associations that have expressed their intentions to register as PWAs are all NTUC-affiliated with PAP politicians as their advisors. It is highly unlikely that MOM will reject them when they apply to register. However, what if a non-NTUC linked organisation of platform workers seek to register as a PWA? Will they be able to register? If SG Riders registers to form a PWA, will MOM allow them? On what basis will MOM decide if a PWA will be allowed to register? Why aren’t the courts the body deciding the outcome of PWA registration?

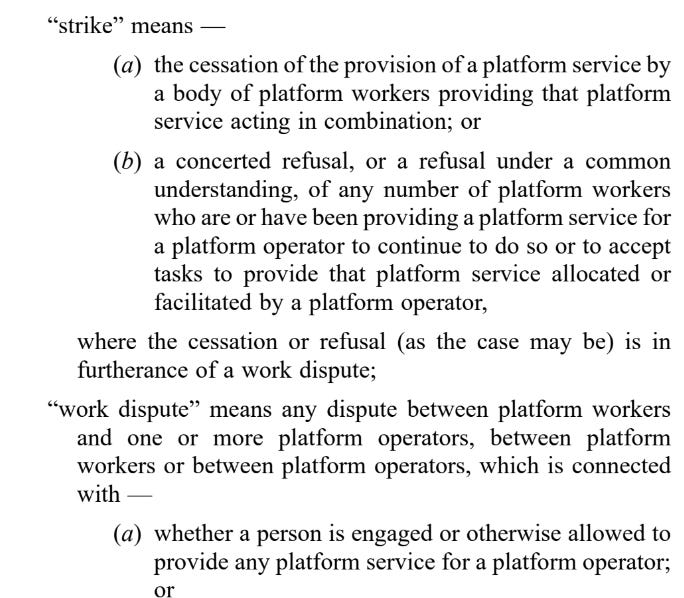

Third, platform workers who are members of a PWA could potentially be more restrained than those who are not members of PWA, in taking collective action. According to the Act, a PWA must not “commence, promote, organise or finance any strike or any form of industrial action…without obtaining the consent, by secret ballot, of the majority of the members so affected”. If the PWA violates this, it is liable to pay a fine of up to $3000.

However, the Act’s definition of “strike” is very broad. Under such a framing, would the food delivery riders’ resistance against the PMD ban in 2019 be considered illegal if they were members of a PWA and did not conduct a secret ballot before going to the MPS sessions as a group?

But if you are wondering why there is even the need for a separate piece of legislation for platform workers instead of just including them under the Employment Act and recognising them on par with any other group of workers, then you’re not alone. Recently, Former President Halimah Yacob posted on her social media that platform workers should be provided the same rights as any other employee. For example, if platform workers fall sick, they will either have to work while sick to earn an income, or forgo income for the days they are unable to work. Without protections for paid sick leave, maternity leave, or a rest day, platform workers have to make very difficult, unfair choices between work and their health and safety.

While I resonate with the view that platform workers should be protected under the Employment Act, many food delivery riders do not. Many riders chose food delivery because of the flexibility it provides. They therefore worry that by being included in the existing Employment Act, they will lose that flexibility and have to adhere to strict working hours and rigid conditions. Instead, many riders I spoke to want platforms to uphold their end of the bargain on flexibility by stopping the practice of penalising riders for rejecting orders. They believe that then, riders will have more power to bargain with platforms about the kinds of orders and fares they get.

The resistance of food delivery riders to being treated as any other employee is, in fact, an indictment of how outdated our Employment Act is (it was drafted in 1968). After all, office workers in Singapore have been advocating for flexible work arrangements (FWA) for years now. In April this year, the government declared that all employers must have a process for workers to request for FWAs. However, there are no penalties for employers if they do not provide workers with FWAs. Perhaps food delivery riders will feel more enthusiastic about inclusion in the Employment Act once it is significantly updated and strengthened to be relevant and responsive to the needs and conditions of modern workers and work cultures.

When did the fight for platform workers’ protection begin?

The NTUC and the PAP say that work on the Platform Workers Bill began in September 2021, when a 15-member tripartite advisory committee was formed to provide recommendations to the government on gig worker protections.

However, I would argue that such an advisory committee would not even have been formed if not for an action that took the entire country by surprise in November 2019 - the ground-up mobilisation of food delivery riders to resist the government’s PMD ban. This group of riders had organised themselves independently, and were not linked to the NTUC in any way.

On 4th November 2019 then senior minister of transport Lam Pin Min announced that PMDs would be permanently banned from footpaths the next day. The 7,000 riders who conducted their deliveries using PMDs at the time were terribly impacted. From 5th to 13th November riders mobilised at various Ministers’ and MPs’ Meet-the-People Sessions, eventually amassing 300 riders at Lam Pin Min’s MPS. While certain concessions were made, the ban was not reversed.

But their mobilisation achieved something else - overnight, a group of workers who had previously been largely invisible in the eyes of the public, became difficult not to notice. The riders creatively turned the MPS into a townhall, submitted petitions to their MPs, and spoke up bravely to the media. In taking these steps, they received significant public support and solidarity.

One year after the riders’ resistance against the PMD ban, the NTUC formed the National Delivery Champions Association (NDCA) to look after food delivery riders’ issues. Officials in NDCA were included as members of the tripartite advisory committee, and conducted feedback sessions with riders. The NDCA is also expected to register as a Platform Worker Association once the Platform Workers Act takes effect. If not for the riders’ organising efforts and the actions they took to register both their grievances and their power, it is not likely that the NDCA or the Platform Workers Bill would have come to be.

Even the NTUC accepts that the Platform Workers Act is a response to the riders’ resistance against the government’s PMD ban. In January 2023, NTUC Assistant Secretary-General and PAP MP Demond Choo said: “There is a greater desire for (platform workers) to organise themselves.. We have seen it locally in response to the PMD ban. The workers came together to demand for changes. So we need a change in legislation to allow union associations to represent this group.”

Riders’ pushback against the initial CPF policy the government proposed

Once the advisory committee was set up in September 2021, they identified three “priority areas to give platform workers a more secure future”:

Improving housing and retirement adequacy

Strengthening financial protection in case of work injury

Enhancing representation of their interests

In November 2021, public consultation exercises began. The NDCA also organised “kopi sessions” with food delivery riders to hear their views about the 3 priority areas. I was a food delivery rider in the Punggol area at that time and I attended several of these sessions conducted by the NDCA. At the session, an NDCA staff (not a rider) brought up the three priority areas. There was general consensus about the value of representation and strengthening protection in cases of work injury but significant disagreement about how to improve housing and retirement adequacy.

The NDCA staff asked us what we thought of making CPF contributions mandatory for all riders. Most riders in that session disagreed, saying that it should be made an option for riders instead of making it compulsory. A rider in his 50s said that he did not have much use for CPF, since he had already bought his house, but it may be an issue for younger riders instead. He brought up how the main reason he joined food delivery was to have a higher take-home pay.

However, the NDCA staff kept trying to convince everyone why CPF would, in the long run, benefit us. I tried to echo what the other riders were saying and urged the staff to listen to their concerns and factor it into the consultation. Another rider however told me (in front of the staff), “Hey..don’t bother. Her boss made up his mind already. Correct?” And to this, the staff nodded her head. I was shocked at what I had just seen.

In another encounter during my deliveries, I met NDCA advisor and PAP MP Yeo Wan Ling and shared my concerns about mandatory CPF with her. Similarly, a debate occurred where she tried to convince me of why the many riders and myself were wrong about how CPF should be a choice, and why she was right. At one point she pointed her finger at me and insisted that I should go and convince the riders I knew that making CPF contributions was in their interest. I was very confused by her tone. Wasn’t this supposed to be a consultation?

As I spoke to other riders about the consultations, many felt the same. They felt that the NDCA-led consultations were not very meaningful. Some riders I knew were so upset about the consultations that they were even thinking of publicly criticising the move to mandatory CPF contributions. We were not against CPF. We were against it being imposed as compulsory for all riders.

Subsequently, in February 2022, an IPS study on gig workers showed that 84% of workers were worried about whether they had enough for retirement savings. The study recommended CPF contributions and a rest period policy among other things - however, delivery riders were not polled on these recommendations, nor were these recommendations informed by deliver riders’ suggestions for how to address retirement adequacy. And in March 2022, Senior Minister of State Koh Poh Koon made it official during his budget speech, that the government was considering mandatory CPF contributions.

In response, a group of food delivery riders came together to create an instagram page known as SG Roo Riders (it has since grown into a grassroots organisation of food delivery riders known as SG Riders). They released a strong statement criticising the Minister’s recommendation to make CPF compulsory for all riders. “In 2019, the government banned PMDs overnight. In 2021, it increased petrol prices. In 2022, should we let the government make CPF contributions compulsory without first guaranteeing a minimum fare for all riders?”

The statement was widely shared by riders and members of the public, and the sentiments in it were repeated during various other engagements riders had with the authorities. Riders even contemplated escalating their response to a public petition signed by many riders. But they didn’t need to.

In November 2022, the government accepted the complete recommendations provided by the advisory committee. All three priority areas remained, with one significant amendment - CPF was only to be made compulsory for platform workers below 30. For riders who were aged 30 and above, CPF was opt-in. This policy was passed into the law via the Platform Workers Act.

If riders did not organise independently to register their opposition to CPF being compulsory for all, and pressure policy-makers on this issue, the CPF policy in the PWA would likely have looked a lot more like what the government had initially proposed.

Yet, riders did not stop there. SG Riders released yet another statement about the updated recommendations. They criticised the advisory committee for not being able to assure riders that their take-home pay would not be affected by the CPF policy, and emphasised the need for a minimum fare guarantee.

In August 2023, MOM sought the public’s views on designating platform workers as a distinct legal class of workers. Should platform workers be included in the Employment Act or should they be classified separately? SG Riders gathered riders from different parts of Singapore and held a forum about this. They summarised the discussion into 10 broad points and submitted it to the government. While there were initially some disagreements about whether riders should be seen as workers, the group of riders came to the conclusion that they supported the proposal for them to be a distinct class as long as they attained certain basic rights such as protection from unfair suspension, the right to freely reject orders, and a base fare in addition to the three priority areas the government had already accepted.

The importance of a growing, independent labour movement

The story of how the Platform Workers Act came to be is therefore incomplete without telling the story of riders’ ground-up organising efforts, and their spirited activism. The fact that they influenced policy while operating outside the NTUC, NDCA, and any of the other channels set up by the government is incredibly significant. In fact, I would argue that they were able to be effective precisely because they operated independently.

This story also offers some perspective on the testy parliamentary debate about the Platform Workers Act - especially WP MP Gerald Giam’s speech on the importance of union independence and the aggrieved responses from PAP MPs that followed.MP Giam questioned whether the PAP’s and NTUC’s close relationship has benefited workers. Mr Giam’s remarks courted harsh criticism from PAP MPs. For example, PAP MP Christopher De Souza accused Mr Giam’s speech of being completely irrelevant to the Platform Workers Act. Minister Koh Poh Koon went so far as to call for the Workers Party to change their name, accusing them of being allergic to working with unions.

But the way in which NTUC-linked organisations conducted engagements with riders about the Platform Workers Act suggests that Mr Giam’s questions about a PAP-linked NTUC’s effectiveness in truly representing workers’ interests are justified. The NDCA’s “kopi-sessions” were an opportunity for riders to share their views, but when there was opposition to what the government had planned, they attempted to convince riders about the benefits of what the government was proposing, rather than being open to amending their proposal. The role of any workers’ association should be to represent the true interests of the workers as determined by the workers, not to persuade them of the government’s proposals. In contrast, SG Riders, an independent association, held democratic conversations with workers, made crucial interventions based wholly on the lived experiences and needs of workers, and were successful in influencing policy change that better protects platform workers.

As the cost of living continues to skyrocket while wages stagnate, a strong labour movement is essential for not just platform workers but all workers. The story of how the Platform Workers Act came to be shows us that such a movement is possible, free of the NTUC’s monopoly.

An independent labour movement is growing in Singapore, and it has proven that it is capable of delivering what workers need - a stronger voice, and practical change. Although it is small at the moment, it is infectious - as workers see the efforts and wins of other workers who take steps to organise themselves and fight for their rights, they too are encouraged to organise themselves and join the fight.

There is much work left for SG Riders and other workers’ associations in ensuring fair working conditions and adequate protections for platform workers. But as we continue these fights, relying on workers’ wits, collective strength and solidarity, rather than the goodwill of those in power, will keep us going strong.

It is a conflict between top-down and bottom-up policy shaping. PAP is not doing badly - Singapore gig workers are already better off than their American counterparts who are freer to union and to voice.

The government proposed to include gig workers in Employment Act but was turned down. It means gig workers still believe the contractor status brings important flexibility that they do not want to forgo. So one has to be realistic about other parts of the job.